General Electric has the same abbreviation as the country of Georgia

One important thing to remember on those days when your superiors have it within their power to delay your violent death, along with their own, and they choose to do nothing, is that right up until it doesn’t anymore, life goes on. If you live near the ocean, appreciate the patient persistence of the breakers, the grandeur of the tides. It’s no sin to pour a long summer evening into holographic parallel terahertz processor powered video games. Go for a swim if you like to swim. Painting with oils is nice: maybe a landscape. Everyone has their own tastes; the irredeemable masochist can always wire a breadboard by hand. Computer science 101. Proof of concept.

Or, when you can no longer distract yourself from the fear of pain and the senseless insult of those who would destroy us all in a vain attempt to preserve for themselves the power to do so, remember that fear forces the mind to prioritize the self, that fear magnifies one’s own significance and erases the possibility of presenting one’s vulnerabilities to another, that fear persuades the subject into self-imposed isolation. So does insult. Propaganda 101. Remember this, and then organize with your peer group—or anyone, really—for mutual preservation.

Quick aside: in real life, very few people have very many dollars

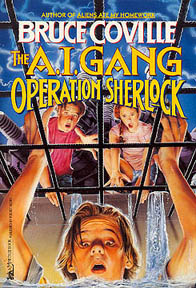

Today we’re discussing Operation Sherlock (published 1986) the first book in Bruce Coville’s The A.I. Gang trilogy, but we’re not going to discuss real-life AI. Maybe next time, if, unlike a cybernetic life-form, I have the stomach.

There’s a simple reason why it’s pointless to compare the significance of AI in fiction, even those flavors of science fiction interested in predicting technological development, to the significance of AI in real life. In real life, the most important facts about AI are not facts about AI at all; they are facts about white-collar crime, about financial instruments, and about the culture of barefaced robber-baron tactics that grew in the years leading to 2008 and then kept growing. Exploitation of labor is not the product of AI; it is the product of business. Fear-mongering is not AI; it is a way for social media companies to maximize ad revenue. Baseless promises about the miraculous processor chip of tomorrow (you’d only be hurting yourself if you don’t buy in today), do not come from AI; they come from business. Ugh; I’m discussing what I said I wouldn’t.

If this article had been written before NYT learned to spell GPT … if I were a rich man, we wouldn’t be this way: a day late and a dollar short.

Green Adventure has the same abbreviation as the state of Georgia so now you can tell them apart

Allow us to manage expectations: The A.I. Gang is not where edgy machine minds hang out listening to ska. If you want that, you know what they say: write it yourself. But hey! the trilogy does take place after the advent of catastrophic anthropogenic global warming, and by the way, if you’re reading this, so do you. Reagan died of old age, whereas all of us …

And Thunberg’s exact point is that individual action, no matter how compelling your sense of entitlement, is insufficient to save humanity, right? Only group decision-making will save us—by large groups—maybe if somehow everyone has a voice. Whoops, did I just say that? Well, this article was never destined for publication in the DPRK, or, like, Kentucky. But Coville understands that survival requires a sort of pluralism, a value of proactive inclusiveness. That value, arguably, does not come naturally to human beings, because the people who need to share the most, never learned to share; and the people most motivated to scrub the atmosphere, are those about to be scrubbed out. We need to disrupt this clout-chasing culture just long enough to reassess.

Have an adventure; you could do worse.

In the dedication, Coville mentions Tom Swift, raising the question of whether the progressive mirror-image of colonial propaganda is still reactionary. (“This is my destiny,” said Tom manifestly.) Tom Swift is a flat character, but boys’ genre heroes are minimally characterized for the same reason shōnen anime heroes are drawn with few lines: to facilitate the boy audience identifying with the hero. (“I would do fine in the Army,” Tom told them straight.) When Tom robs ancient treasures, he improves the world, for the same reason that sex is an unknown topic to him: because Tom is pure. (“My girl back home would love some of these Scythian artifacts,” said Tom, rushin’ into the museum.) Tom is not upwardly mobile because he, and his America, are already perfect. (In this exotic locale, Tom’s phenotype was fairly noticeable.) By coincidence, the very best Twitter accounts owned and operated out of St. Petersburg use the same tropes today.

In contrast, a team adventure has at minimum two plots: the adventure, and the gluing together of the team. Because the adventure in Operation Sherlock is challenging, it proves to the heroes that they need one another. But because the other children are frightening and grotesque, they each learn humility, learn to tolerate the initial awkwardness of making friends, even though their American upbringing taught them only individualism and worship of the fragile ego.

Climate fiction is persuasive when it works but, paradoxically, few writers know a successful formula. Where’s the emotional payoff for participating in the global energy revolution, loser? Coville, shockingly, noticed that setting aside ego is a hook, and that if—if—your formula for some kind of near-future green sub-genre were, “The heroes must set aside their ego to survive, repeatedly, and it never ends,” that would by sheer coincidence also describe reality.

So divest your fossil fuel portfolios, charge up your most efficient e-reader, and log off the app where bots posing as your peer group offer you a subsidy of a million bucks to vote laissez faire. Sea level is rising; let’s dive into climate fiction.

Synopsis

Like all good team adventure, we’ll begin with a straightforward dramatis personae, in anticipation of all the personality clash. Trapped together when their respective parents join a secret project on tiny, fictional Anza-Bora Island (got to be a contraction of ANZAC and Bora-Bora, right? But this is ironic: Bora-Bora and local capital Tahiti are not territories of any American Empire but a collectivity, naturally, of France) we have the following.

Twins Roger and Rachel become the team’s glue—everyone else suffers only child syndrome. Roger possesses social intelligence, which is undervalued and underestimated. Rachel studies psychology and mnemonics and is her own experimental subject. (In this world, like in the ‘hard’ SF novels of Poul Anderson or Larry Niven, ESP can be developed by practice, practice, practice.)

Wendy Wendell the Third (WW III, just like the upcoming war, haha …) wore baggy sweats way, way before it was cool, and eats a smash-burger for every meal. Her irreverent robots might be inspired by Blade Runner (1982) or Gremlins (1984).

Tall, clumsy Trip is stunted by privilege. From his technically adroit mother he’s learned computer science. In his artist father, he has witnessed inner peace, concluded that that’s sissy, and has learned male insecurity instead.

The (half) black kid with the basketball dreams of the terminally short, is Ray Gammand. Emotionally tough, a good troubleshooter, still he, like Trip, has something to prove.

This concludes Chapter One. But then, all-American Hap Swenson appears as if in a barista AU, masculine in every way: blond, tragic, car-obsessed, brooding, proud, isolated. He could be Neal Stephenson’s grandpa. He could play the protagonist in the Star Wars prequels. The team’s only public school kid, he’s worse at teamwork than any of them.

In Chapter Two, they survive the story’s first bombing by the facility’s secret saboteur, then break for snacks. The kids behave selfishly, showing off skills and gadgets, including Ray’s current detector, which in Chapter Five alerts them to a surveillance device attached to Rachel’s shirt collar.

The reader knows, with a little page-flipping, that every adult on the island had the opportunity to plant the bug at some point that day. We can officially declare: everyone is a suspect! That makes close to 120 people, seventeen of whom have security clearance. Those are the facts from pp 57-58.

And in Chapter Six, Rachel delivers these facts, including the names and specialties of those seventeen.

So the others reply, golly, you’ve unlocked eidetic memory? In this moment, unlike our other respective skills, that is not only awesome, but relevant, therefore you may have something new and greater than our participation; you have our respect. No longer just a bunch of rival entitled snots, they are now a team, a secret research project within the secret research project.

It falls on Roger in Chapter Seven to lay out the plan of action. They’ve got a crime to solve; the suspects list is large, but finite; they’ve got a supercomputer; it’s dark and they’re wearing sunglasses. The five of them will program the computer to tabulate data on the suspects. Genius! They will call it Operation Sherlock. Oh, yeah, and on the side they’re gonna develop a self-aware machine; everyone’s doing it.

They formally meet Hap when he’s driving too fast one day, and causes Trip to roll his (electric) dune buggy; he stops to help but still gets the freeze from the rich kids. To spell this out, the book has twenty-one chapters. Roger says the name of the game in Chapter Seven; Hap, contrasting James Dean, skids to safety in Chapter Eight; but he doesn’t join the team until Chapter Fourteen. The entirety of Act II is taken up with this “How Will I Know (If He Really Loves Me)” drama.

The reason to spend one-third of the book on this subplot is to convey a message of pluralism. The elite children swoon over their privilege of mainframe access; Hap sends ominous messages as a prank and makes them mistrust the computer. Wendy wants burgers without any commitment; Hap flips burgers but makes her feel guilty for using him in this way. Trip and Ray will never be blond and bad like Hap. Roger smiles; Hap frowns.

Hap exists to remind the other five (and the reader) that there was a time before the A.I. Gang, a time when they, too, were alone, when they, too, depended on someone else to take a risk by freely offering unconditional friendship.

In Chapters Ten and Eleven, Trip and Ray show us around the facility’s tidal power plant, which works using a bizarre technology that Coville has got to have made up out of whole cloth; please, someone, tell me if you know otherwise, but there’s never been a design anything like this; it’s inefficient; it’s insane; and it just might work.

In Chapter Twelve, the kids land on the doorstep of the resident expert in “code systems,” Stanley Remov, and his “friend,” Armand Mercury. Remov delivers exposition re the team’s nemesis, Black Glove. The story problem of the trilogy is: who is Black Glove?

With Remov’s help, in Chapter Thirteen the kids surveil an abandoned house—already a far cry from hacking arcade games. They now understand that the most reliable method of surveillance, and sometimes the most appropriate, is to get off your butt and follow somebody. In an intercut scene, we learn that the saboteur has only now constructed a bomb big enough to destroy the computer mainframe as well as all the scientists (and their families). In Chapter Fourteen, the team finally confronts Hap.

Fans of John Le Carré recognize this beat: the debriefing that changes everything. Because Hap’s messages leave no other trace, they have already deduced that his method is a back door, i.e. purpose-built surveillance software. “How does the back door work?” they ask. And he replies truthfully, “I don’t know.” He only discovered it; the back door was already there.

The debriefing concerns four (and a half) story problems: the bomb from Chapter Two, the bug from Chapter Six, Trip’s dune buggy from Chapter Eight (the day after the crash, the buggy was inexplicably intact) and the anonymous messages (and the back door). Hap repaired the buggy. Hap sent the messages. But he did not design the back door. So, in the approved mystery novel way, by the process of elimination, the team has proof that one (or more) of the adults is responsible for the bomb and the bug (and the back door; that’s alliteration).

Surveillance on another kid is one thing; but it would be foolish to go after Black Glove by themselves. In Chapter Fifteen, they ask for help from the project director, Dr. Hwa, but he brushes them off. Only Remov ever takes them seriously.

In Chapter Sixteen, Trip and Ray have their courage bolstered by Hap, and they all tail a suspicious person. It’s the saboteur. (They caught her!)

She locks them inside a convenient tidal compartment inside the tidal power plant and, in Chapter Seventeen, leaves them to die when the train when the tide comes in. The saboteur is Dr. Sylvia Standish, the power plant operator; she was a Christian fundamentalist all along; creating a machine intelligence goes against her faith. Jesus doesn’t only love guns and petroleum; He’s okay with green energy, too.

But Dr. Standish did not, and had no reason to bug Rachel. Now Trip, Ray and Hap can prove that Black Glove exists independently from the saboteur—if they survive!

In Chapter Eighteen, water begins to pour into the compartment—agonizingly slowly, yet terrifyingly quickly. A classic. Roger and Rachel use deduction to establish their missing friends’ location; they gather with Wendy at the power plant. (The girls have arrived to rescue the helpless boys.)

In an intercut scene, we learn that, when Dr. Standish planted her new bomb inside the mainframe, she accidentally disconnected a secret radio transmitter belonging to Black Glove. Black Glove now rushes to fix it. Hap convinces Trip to show courage in the face of certain death, and they sing, “Many Brave Souls [sic] Are Asleep In The Deep,” an error which I would like to take credit for catching personally—it should be, “Hearts.” The text doesn’t specify which version; therefore Chet Atkins is not ruled out. Wendy breaks down the power plant door using traditional California karate.

Roger confronts Dr. Standish. She attempts to intimidate him, using primed concepts such as grown-up and administrator. Roger recognizes what she’s doing, and intimidates her right back, using the primed concepts that he is defending his friends and that she is obviously guilty of something. Dr. Standish is not an international super-spy; she’s an American, and falls for this trick immediately, revealing not only that she built the first bomb but that there is now a second. She escapes. The kids steal her notebook, which confirms her admission of guilt.

Chapter Twenty is the climax of the story. Wendy steals her parents’ VW (everything in their household has a W) and the team uses it to break down the doors of the computer center. They drive down the halls in a scene unmistakably reminiscent of the False Eizan Electric Railway scene in Uchōten Kazoku by Morimi Tomihiko, in which a man who is about to die goes on a drunken high-speed drive in a magical streetcar that is also his shape-shifting second son while bellowing the mantra, “What’s fun is good,” and which was published in 2007 in Japanese and not translated to English in any form until the anime in 2013, so what’s the shared reference? At the doors to the mainframe, the boys, especially Ray, fistfight the remaining guards, reclaiming their masculine dignity. The kids enter the mainframe.

Rachel and Roger are in the lead when Black Glove catches sight of them, and they witness Black Glove’s silhouette, from afar, but the light is very dim and there are “wires and crossbars” in the way. Black Glove flees. Rachel identifies the bomb; Roger disarms it. Rachel also discovers Black Glove’s transmitter. The transmitter self-destructs. Chapter Twenty-One, denouement.

Dr. Standish steals a motorboat and gets caught. Dr. Hwa personally thanks the team, a great honor. They plead with him to believe that the transmitter was built by Black Glove; Rachel is a sensitive and it burned her hands when it burned itself. He concedes that the transmitter was real; but reveals that a second motorboat has turned up missing, so presumably the spy is gone, and anyway he will increase security in the Book Two. In an epilogue, Black Glove, obviously still on the island; reflects that since it was the kids who discovered the transmitter, opposing the kids will become their top priority … in the next volume about The A.I. Gang.

If you were to write a partial list of attested motivating factors for defection from a Kremlin intelligence agency in any century you choose

That’s gay.

Is this climate fiction?

Actually, there is something to say about the defector. In Chapter Twelve, the kids come to Remov with a concern about cybersecurity—his field—and he takes them seriously. The fun of the story is in testing the kid/adult boundary, so the one adult who admits that Black Glove is real, calls the kids into the adventure twice, once by exposition and again merely by existing. And who listens to Cassandra? Another outsider. The story only works because gay people are omnipresent, and persecuted. But then, the sexless quality of the entire text has the odd effect that Remov’s closet door is like the unicorn: visible only to those who search, and trust. Remov and Mercury are only ever “his friend,” “my friend,” “the two friends.” Certainly, silence is death. In 1986, epidemiologists understood AIDS and virologists had isolated HIV, but the authorities responsible for warning the public intentionally quashed this information, so we can only speculate what Coville’s information space was like at that time.

But for a middle grade book that stays on the safe side of Don’t Ask Don’t Tell, this gay romance is not the worst possible representation. There is characterization. The two men are both intellectual, educated, successful; they appreciate material comforts; they are able to live together due to high status. Each provides accountability during the other’s healing process: Mercury frequently performs the mechanical operation of smoking a pipe, with soap bubbles; Remov was traumatized by his “years in intelligence work;” he frowns; he drinks. Sometimes he lashes out; Mercury communicates the hurt in a gentle tone of voice and gives him space. They are thoughtful, dignified, adorable.

The gay story is inseparable from the defector story, which is undeniably relevant to the present day. On Anza-Bora Island, the one person who can accurately explain to you why and how your server is being hacked is the Russian expat—which Russian expat?—the one at odds with the virtues of old Tom Swift. Well, this gratifyingly reinforces what we know. It also shapes the story more firmly into a division between a mainstream and everyone else, a mainstream from which one may be excluded arbitrarily and unfairly, a division that at times must be crossed in order to survive, which can only be crossed with teamwork. When Remov is at his most honest, he is at his most childlike, in that his truth is unacceptable to the authority figures responsible for protecting him.

Is this climate fiction?

But back to our scheduled program. Comparing the kids’ lives at the beginning and end of the book, what changes? Yes, they form a team. But the specific choices of imagery in this science fiction story now fall into place. These are not public school kids, but the offspring of the best minds in the country. All they have to do, to gain access to information age wonders such as this nostalgic Pacific Theater military intelligence daydream, is wait to grow up. But the very power of the mainframe, its massive publicly funded contract and its opaque corporate management, the power to destroy the world or save it, the power with which they are quietly obsessed—nerds—is also the reason they demand their right to question the purposes to which that power is put. Children wear watches powered by body heat; adults build power plant full-scale prototypes.

In this story, pluralism is so important that it is worth pushing against the child/adult boundary to change yourselves from isolated putative insiders into pluralistic outsiders. And by the way being gay, gay and traumatized but doggedly pro-social, is another metaphor for the same thing. We can assume given the publication date that homosexuality is criminalized in both the Soviet and the American military (still in this unspecified near future year). Remov knows that other scientists see him as frightening and grotesque; this promotes a value of pluralism in him, which he expresses as a willingness to organize with frightened children although they are his inferiors and he would be within his rights to brush them off.

I’m confident Coville intended the child/adult boundary to be felt, and for crossing the boundary to be felt, because it is present in the story on two levels. First, within the story world, as in most adventure, transgression already takes place in the heroes’ minds when they organize as team, because they communicate their true priorities without prior permission from society; in this moment the eventual rule-breaking becomes not only effortless, but conceivable. The reader understands the power of teamwork to save the heroes’ lives when society cannot, so the reader also reconceptualizes transgression within the story world as incidental. Second, on rereading, especially at an age older than some of the villains, the idea that real kids should have experiences like these is impossible to take seriously, yet the reader, by opening the book, accepts that the fictional kids will take on adult responsibilities at some point. The reader is primed to inquire how the child/adult boundary works in the story world, because the difference from reality is highlighted.

My claim is that this portrayal of adventure, and the thrill that it provokes, functions as a metaphor for good advice on climate action.

The story works as climate fiction only if “the adventure” is indeed a metaphor, because in reality all of us are treated like children when our truth, our pleading for our lives, prove unacceptable to the judges who allow the fossil fuel corporations to purchase the politicians who allow fossil fuel corporations to delay the transition away from fossil fuels. In reality, the task of those who want to live is to unite enough individuals, so that the group can achieve the power to build a clean energy economy that downwardly distributes basic human needs, in order to minimize mass death during the ongoing crisis, which is necessary to hold together the coalition we are talking about.

In reality, we are not like children after all, because what prevents us from doing this is not youth or ignorance, but our own racism, greed, in a word, entitlement. That, and gerrymandering and a court system packed to the gills, but how did we get here, if not by the lack of pluralism?

Metaphorically, everything you need to know is communicated by the image of uniting with fellow outsiders whenever it becomes impossible to pursue pluralism within the mainstream—like now, for instance, like always. Metaphorically, we are all like gay defectors, because they share what they know. We are all like The A.I. Gang, because they go on adventures, because this time the adults are not going to do it for them.

We are all like The A.I. Gang, because in their egotistical and grotesque teammates, they see themselves, and are inspired to learn humility enough to form a coalition. Perhaps, as we try to broaden our own coalitions, our limitations were the friends we made along the way.

Days at the beach

Or, perhaps we can learn to work on ourselves first.

In the novel, an unspecified amount of time passes in Chapter Fifteen after the team has finally coalesced. They have “a nagging feeling that they were working against a deadline,” yet they are happy. Coville delivers exposition on their daily routine: hacking, scrounging, building, a drive, a picnic, a swim, return to work refreshed, scuba lessons and hiking, in the evenings arcade games or classic films. What genre does this come from? It’s a green cyberpunk near-future, but it’s nostalgic military Americana. It’s an elite fantasy but a classless fantasy. (Post-class?) It’s a spy story, a wistful glimpse of civilian bliss reflected in the found family during the operation. If only it could last.

This is the image that I anticipate when I reread the novel, not the gadgets and skills, not the death trap, not the climax. There’s no practical reason most people’s real lives couldn’t resemble this schedule, give or take the joint American-Chinese-Soviet occupation of a Polynesian island conveniently free of Polynesians. Give or take the clean energy changeover that has not yet happened in the story, this idyllic half-industrialized setting could be built anywhere.

The days at the beach also depict a detente re the child/adult boundary. The kids are neither lonesome nor suffocated; they are fed, clothed, and turned loose, sometimes supervised, sometimes a phone call away. On the island, there are no drugs, no interpersonal violence (only mass violence, haha), no poverty, no abuse. This is a fantasy of the world that adults, with a sufficiently serious pluralist mindset, could create for children, but parents can never do it alone, and not by prioritizing children alone; it will take all of society working for all of society.

In the middle of the novel about humanity’s power to save or destroy the world, the days at the beach remind us why it’s worth the trouble.