An Etymology of Childish Things

There is a room whose walls billow muslin. Sun unseen, illuminance shuns human hands. As suspended in the airy night of mind, where primally structure the technical, so here, we work by feel.

We aspire to bridge heart to heart, a feat of engineering proof against earthquake’s resonance. Our primary model resembles a clothespin, an ovoid, root vegetables, the little goddess. If we could see ourselves! We talk to the model, carry it in the crook of our arms, sit down across from it, respond to its concerns. We show hospitality to the model. We serve tea.

The model need not be a model; it could be a rock, a sock, a psychological projection flickering atop a beleaguered cousin—or nothing at all; it could be imaginary, friend. The model does what we say it does, says what we say it says. What kind of friend are we? At dawn we make our bed; at play time we make up our mind. In the room where walls waver, we make trials; we make errors; we grow.

Puppet derives from the diminutive of pupil.

Muppet derives from the diminutive of mop. We can’t be all serious all the time.

Machina ex Thea

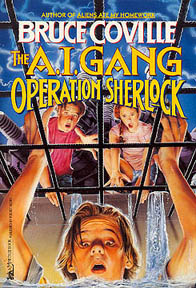

How to write the second installment in a trilogy? Chalk up all of the story’s action scenes and lever them onto a moving stairway: this is escalation across the board. We readers want a book to reveal the tenderness of the human condition—for twelve pages, until it becomes bo-ring. Double meanings are out; sugar crash is in. C’est en effet une pipe after all. But, what do I escalate when I escalate … everything?

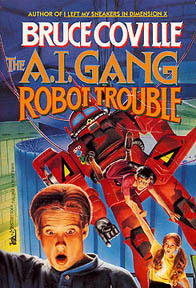

Originally, The A.I. Gang trilogy was outlined as a quartet; Robot Trouble was Book Three. Flashback scenes from the deleted second book appear in this one; the conflict between the A.I. Gang girls, Wendy and Rachel, almost all takes place offscreen; it passes the Bechdel test, but the simplistic imagery approaches the trope of a catfight. I find four loosely braided threads here: 1) the catfight, where like in an art school darkroom, the background does not develop in any detail; 2) classic science fiction imagery of mechanical servants; 3) a musical theme that tests the limits of communication and empathy, a Coville favorite; and 4) the spy story, stating the theme of fun, or power, or “the social and the somatic.”

Not one of the four threads convincingly resolves; yet, to begin Act II, the heroes for the first time go on the offensive against the main villain. Team leader Roger repeats his words from Book One: “Stand back, everyone—I think I’m about to be brilliant.” The plot of Book Two is: the A.I. Gang baits a trap for Black Glove using an innocent orbital traffic control robot named after the Greek goddess Euterpe. (The rocket that will launch Euterpe into space is the perfect place for Black Glove to conceal a new radio transceiver.) The characters improvise a rickety structure out of mismatched parts, just as a writer does when he rebuilds two novels into one, or a mad scientist when he violates the boundary between man and God.

The second novel in a trilogy lives in the moment. All that offscreen stuff? That’s the stuff that you can no longer do anything about.

Synopsis

The author loads several metric tons of robots into this one little paperback, not one of which ever operates the way it was intended to, hence the title.

Nemesis and comic relief Sergeant Brody has a bunch of monstrous new security robots patrolling the facility’s warehouses, one of which is depicted on the cover terrorizing a bunch of children, perhaps authorial self-actualization. But “Deathmonger” fails to guard any electronic equipment against being “temporarily repositioned”—beginning with itself. Other adults who indulge in the creation of servants and frenemies include Ray’s dad, who prototypes all of his video game characters as cybernetic toy monsters—maybe he’s a poor sketch artist—and A.I. Gang ally, Soviet defector Stanley Remov, who has a gentleman’s-gentleman type for his chess opponent.

And the story’s inciting incident is when Rachel meets Dr. Leonard Weiskopf’s creation, Euterpe, daughter of Mnemosyne, which does not appear in the cover illustration, likely because its design resembles litigious monopolistic megacorporation prized property, Artoo-Deetoo. Euterpe’s purpose is to calculate safe orbital paths for humanity’s congested satellite inventory. But it tragically fails to harmonize the orbits of a swarm of tween nerds; I guess that task, like many, requires the human touch.

Speaking of human defining features, Weiskopf’s musical talent charms Rachel in Book One; now she herself begins studying music. A career flunky of the military industrial complex, Weiskopf warns that emotions are easily manipulated, that this is music’s “dark side, if you will. Everything has one, you know.” To all you foreshadowing enthusiasts out there, you’re welcome in advance.

Rachel eventually confides in Weiskopf about the catfight. “More friendships are lost over careless words than anything else,” says Weiskopf pointedly. “If there was only music, we might all be better off.” On the surface, this contradicts his earlier claims that war and hate arise from passion (claims that Ibram X. Kendi would rebut: hate arises from opportunism), but Weiskopf shows empathy by giving voice to Rachel’s beliefs—at that moment, she would trade her words for music in a heartbeat.

What Weiskopf admires about music is its connection to human passion, but this power is never tested in Robot Trouble. Where is the scene in which passion per se is the decisive factor in a spy conflict, or an interpersonal one? In the novel as we have it, conflict is resolved by action, dryly, in moments of repressive silence, which strikes this reader as horrifyingly realistic.

This includes the new miniboss, who tiptoes into the narrative in Chapter One. For every incentive of Black Glove’s to play a slow game, the Fleming-derivative post-Soviet pursed-lipped mercenary has an incentive, as they say, to move fast and break things. Ramon Korbuscek defines Robot Trouble as a spy story, giving the heroes (and the reader) an excuse to play with spy toys. His cover identity, Brock A. Rosemunk, is an anagram. If you caught that at age 10, dear reader, your future is as bright as Nancy Drew’s herself. He falls to his death in Chapter Twenty-One, in stark contrast to the miniboss from Book One, who gets arrested. If that’s not escalation, what is?

Korbuscek analyzes the tidy reception area kept by secretary to the project director, Bridget McGrory (too tidy). He sneaks into the office of power-obsessed Sergeant Brody, puts his feet on the desk, and snoops through his mail. His former mentor is none other than Remov; Korbuscek hopes to “finally get rich on what I learned from the old man,” ironically, by photographing Remov’s classified documents. (Get it?) Korbuscek applies makeup; climbs through windows; picks locks; tells time by the moon. The heroes never see these things. The narrative is «глаз в небе»; glaz v neve; ein Auge im Himmel.

Remov loses a fistfight with Korbuscek at the novel’s midpoint. Remov only survives by speaking a trigger word; Korbuscek is under post-hypnotic programming, and flees in terror. Remov enlists the team’s help: it was dark, and Korbuscek will have “had his face altered half a dozen times by now.”

Mercury happens to arrive at the infirmary while Remov is already holding court with the kids. To gain entrance, Mercury must shout down Dr. Clark, who wants Remov to rest. Suddenly vulnerable, prideful and enraged, Mercury says, “I will not be prevented from seeing my friend.” Reading as an adult, this is the only line in the series that strikes me as an overt portrayal of the gay experience.

In the Act II subplot, Remov teaches the heroes to chart all their clues to Korbuscek’s identity using paper and pencil—the table is reproduced in the text to make sure the reader learns this method. But they are outfoxed. When his decoy gets perp-walked away, Korbuscek is inwardly beaming. During the novel’s climax, he still has not been ousted from his cover identity as a security officer; he gloats about his access to any place in the facility.

At the story’s climax, a sprawling three-chapter romp, the team stakes out the rocket launch silo, drawing Black Glove into their trap. But Korbuscek’s mission, ironically, is to hack Euterpe; and he infiltrates the silo via an unlit network of tunnels that he memorized beforehand (a detail that could be one Fleming trope too many, or a refreshing, unexpected dash of The Tombs of Atuan). Like in Book One, it is the miniboss who locks two team members into a deathtrap together, this time Hap and Roger, who catch Korbuscek on his way out of the rocket, successful in his mission. (That robot sure is in trouble now).

Korbuscek knocks out Hap and Roger, not with his fists but with sleeping gas, and leaves them tied together with “thin but incredibly powerful polyester twine” at the base of the rocket to be incinerated. Meanwhile, Rachel leaves her post, and as a result confronts Black Glove, an event the kids were trying to avoid. Black Glove does knock out Rachel with a “sudden blow,” and leaves her locked inside the rocket with no tools except her pennywhistle and the muse of music.The boys, after much philosophizing and reassurance never to give up, free themselves. Rachel, in contrast, wakes up alone, and must calm herself using her Mentat training. Now she sends an SOS—Euterpe is broadcasting on its own dedicated radio frequency, and expands the pennywhistle notes into a chamber orchestra, but retains the rhythm—which is what summons Korbuscek to reenter the silo, because he believes, incorrectly, that his tampering has been discovered.

The remaining team members heroically halt the launch. Wendy gains ingress by amassing the security robots, which the team has long since hacked, and slamming them into the control room door until it (and they) break down.

A fistfight is a rare occurrence for Coville, and Robot Trouble has two, another form of escalation. In Chapter Twenty-One, on Fleming’s inevitable metal-grate catwalk, Korbuscek soundly out-fights Roger and Hap, this time using an unnamed but still vaguely racist style of martial arts. The boys, after messily sawing through the zip-ties earlier, dangle from the catwalk, their grip impaired, distressingly, by their own blood. Remov saves them by speaking Korbuscek’s trigger word again, into a very convenient loudspeaker. No one ever asks him, afterward, what the hell that was about; they’re all distracted. But among the adults who helplessly watch the fistfight from the control room … is Black Glove, whose own tampering with the rocket is eventually blamed on Korbuscek, ensuring that the kids will hack again next week in another episode of The A.I. Gang.

The Trouble With Robots

or, Hello, Dolly

The trouble with robots is really trouble with us. “User error,” as they say, and that error is projection. The mafia lapdog believes everyone is ripping him off. The spook believes he’s under the tightest surveillance of all. In that case, he is, but the reason he believes it … is that that’s what he would do, if the roles were reversed.

So here. Elegant, polite nerd, Hugh Gammand, knows that what people want, himself included, is Thugwad the Gross; that’s why he can’t restrain himself from tinkering at the breakfast table and that’s why Thugwad destroys his fried eggs. The reason Rin Tin Stainless Steel’s functionality is negated by incessant pranks, is that precocious buttoned-up prep, Roger, has no other outlet for his immaturity. Deathmonger is everything Sergeant Brody wishes he were: big, scary, mindless. Dr. Weiskopf attained his scientific career only after military service in which he would “kill without mercy;” and Euterpe’s high-minded purpose is subverted to encourage global thermonuclear war. Remov, whose own gender presentation is not above reproach, remarks of his chess opponent, Egbert, “Gender’s the one thing they [robots] don’t have—and never will, if we’re lucky.”

Rachel is frustrated in all of her attempts to create harmony: with Wendy, with her protective single father, with her male teammates who can’t form sentences in the presence of the beautiful female scientists. But she learns Euterpe’s musical pitch activation sequence, and studies functional tonality.

Every time irredeemably spoiled, uncultured Wendy gets her hands on a robot, including Deathmonger, she puts a pretty red ribbon on its head and instructs it to sing its horrible heart out, just as her irredeemable yuppie parents have done with her. They are her fellow aberrations.

Even Korbuscek has been sent with a device to end life on earth, precisely because he is a mercenary. Only a sociopath could install such a device. When he hears Euterpe’s music, “nothing had affected him like that in a long time” … well, that’s his whole problem!

The human insecurity revealed by so-called Robot Trouble reveals an underlying loneliness. Uncertain of good reception by a friend or partner, the characters instead model behavior using a doll. All they want is for the doll to accept them as they are. Unfortunately, it’s easier to direct radical acceptance at Artoo-Deetoo than at a real person. (No offense, buddy.) The novel is a meditation on friendship, where personality flaws coexist and harmonize. Gammand and Korbuscek, WW and Weiskopf are each wrapped up in an egoistic little drama precisely because they crave inclusion. Like all of us, they would be happier if they paid more attention to the people around them.

No Robot? No Trouble

A cold war snaps and crackles between unkempt California wunderkind, Wendy, and preppy Massachusetts team player, Rachel. The catfight is initiated in Chapter Twelve when Rachel, without thinking, spills Wendy’s biggest secret. I guess Rachel is so accustomed to obeying the rules and therefore having nothing to hide, that she forgot Remov would be duty-bound to report on them.

During the climax, it is Wendy who recognizes, just in time to save Rachel’s life, that the procedurally-generated music on the loudspeakers is seeded by an SOS: Rachel extends her mind in a plea for comprehension, and Wendy meets her on her own grounds, indeed without verbal communication, that oh-so-symbolic human unity. In the epilogue, the repayment cited “in lieu of a long-overdue apology” is indeed Wendy’s deciphering of Rachel’s SOS.

The puzzle is this. Rachel’s original slip-up makes Rachel look bad; Wendy is fine. Yet, the drama emerges after Rachel apologizes. Instead of accepting the apology, Wendy blows up in her face, implying that something deeper has offended her. So two possibilities spring to mind for what Wendy cannot forgive.

Maybe it’s Rachel being so entitled, so obedient, so accustomed to having the adults on her side that she can lower her guard, whereas Wendy lives in a vigilant world of disdain for the rules, disdain for adults, and disdain for tofu. When Wendy rips into a burger, she embodies the defiant spirit of unschooled human potential. She needs the team, because they enable her lifestyle of relatively civil disobedience. But Rachel, and therefore an important subset of the A.I. Gang, cooperates with the very institutions—the military industrial complex, gender, laundry—that have inflicted upon Wendy a cleaning maid robot, a bedtime, and her mother’s dictum, “This isn’t punishment, dear; it’s nutrition.”

The novel does not portray Wendy in the most sympathetic possible light.

Frustratingly, we never examine how Wendy squares her anti-authoritarian ideals with her life of privilege, so perfectly encapsulated in the example of the computer mainframe, where a twelve-year-old can hack into a higher security area only if she is given unsupervised access to a lower one.

The second possibility is that Wendy is jealous of Rachel. The usual regressive catfight trope would have this structure: jealousy over male attention, or over attractiveness, or over station. But if Wendy of all people felt that Rachel unfairly uses her prettiness and sweetness to obtain advantage—and we’ve never seen Rachel do this—that would never prevent hard-nosed realist Wendy from stating the issue aloud. The girls’ prior relationship is nothing like this: Wendy respects Rachel as a fellow nerd. Just, a nerd who habitually grips flatware.

My interpretation of Wendy’s wound is that Wendy perceives Rachel not as an anti-libertarian collaborator, but as an anti-feminist collaborator. It is not male attention Wendy is jealous of, but female solidarity. Positive reinforcement from others for Rachel’s feminine-coded traits is fine; but for Rachel herself to feel positively about her own feminine-coded traits is a dereliction of duty. True, Rachel’s crime, telling Wendy’s secret to Remov, is not gendered. (Maybe in the deleted second book, the original crime was “being too girly.”) But Wendy looks to women (including her very respectable, controlling mother) for protection as she pursues her future in STEM, and she looks to women to reinforce of the righteousness of women’s liberation.

There is a rich unfulfilled potential in this unique relationship, each girl with exactly one female friend, a condition of responsibility and influence over each other, which neither one entered into voluntarily. What is the nature of gender in inherently asymmetrical interactions: mentor and pupil, old money and new? Does gender necessarily reinforce inequality, or is it sometimes incidental, even lenitive?

Wendy’s ideals are compelling because they are intersectional. She doesn’t want to be superior; she just wants to be left alone. Just to be left alone, a feminine girl such as Rachel must do twice as much as a boy, but a gender-nonconforming girl such as Wendy must do ten times as much. That’s the premise that deserves its own separate book.

What Is the Ionosphere But Liminal Space?

The defining scene of the trilogy takes place in Chapter Eleven after the kids temporarily reposition Deathmonger. In order to reverse-engineer the thing and create a remote control, they require privacy, so their designated work site is a convenient cave that no one else knows about. In another article somewhere, the author explains that the imagery of this scene sprang from his mind one day fully formed: the cave, shadowy, sheltering; the kids sharing group inclusion due to their shared secret; and the work, scientific work by which such humble gadgets as lanterns and screwdrivers open a service panel to a wondrous future. The cave bares “great rocky fangs,” which throw “shadows like giant fingers groping for a lost dream.”

This is somatic storytelling. You had to be there. The characters feel, physically feel that working in the cave will give them power over their environment. Our actions must succeed, and our actions must be our own; this is power. And in the moment we know in our mind how to obtain power, a feeling manifests in our body, and this feeling is fun.

We trace a line through the Hardy Boys back to Tom Sawyer. We have identified the missing ingredient in the Montessori system, where kids spend the day within the white plaster walls of a soft, sanitary play room. A schoolhouse is still a bounded environment. Human beings discover a sense of self only after emerging from a liminal space.

Children play with dolls to learn about society. The doll is our puppet: it behaves as we imagine it to behave. Play is theater: by observing play, we observe our real social world. Play takes place on the threshold of “the unreal and the real;” it is liminal. Robot stories have only ever been written by people who were already familiar with dolls, with puppets, with toys. The delight in robot stories stems partially from the liminal nature of robots themselves: robots are lifelike machines, animated but inanimate. When a robot frustrates its creator, like in The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, the dissonance between expectation and reality reveals the creator’s imagination, which they had thought private, for all the audience to see.

I’m not the first to assert that grown-ups project their own minds onto their toys, toys ranging from the Met Gala to nuclear submarines, from judicial robes to shell companies. We’re all in robot trouble out here. But that doesn’t mean that we have to take high-ranking persons seriously. We’re not under post-hypnotic suggestion; and the behaviors of the powerful are truly ludicrous. If we must die, best to die laughing.